Interview: Michael Langan on Replacement Animation

How A Very Niche Animation Style Became (and Unbecame) His Trademark And How Our Relationships With Art and Meaning Have Evolved And Criss-crossed.

And hello to all my new followers from [checks notes] Fox News….? I hope you find what you’re looking for. I’ll probably post more about the Man Enough campaign and its fascinating ripple effects at some point. But today’s newsletter is a long conversation about artifice vs storytelling with artist and filmmaker Michael Langan.

In all honesty, though, if you started following me because you like my work/vibe, thank you! If you started following me to trash what I do… I’d encourage you to… not do that? This newsletter is about art, design, politics, culture, and the things that bring me joy. If your vibe is trashing other people on the Internet, my challenge for you is to define yourself by the things that bring you joy instead of by yucking other people’s yum.

Anyhow… Michael and I have been friends and collaborators for a long time, and his work always inspires me. Here are a few of my favorite collaborations – both with me as Creative Director and Michael as the writer/director.

Also, in a weird way, even though this interview is with Michael I feel like it’s some of the most in depth I’ve gotten online about my personal relationship with art and commerce.

Alrighty. If you’re a creator, director, an animation nerd, or love process, I think you’ll enjoy this sprawling conversation. If not, maybe just skim through and watch some of the videos. There’s a lot of cool stuff in here.

Jacob: Hellooooo, Michael! I’m excited to chat with you and I'm so interested in replacement animation. Before we get into that, can you give us a quick background of your path as an artist and filmmaker?

Michael: Yeah, I came to film from a technical angle. I was excited about all the pieces that comprised film: photography and design and music and sound design and drawing and all that stuff. I wasn't as interested in story. So, the films I first got really excited about were pretty mechanical. Playing with time and space in a technical way felt exciting to me. If my first films had any kind of meaning, it was almost incidental. Although, looking back now, I think there's more to it than I gave myself credit for early on.

Michael: I graduated from Rhode Island School of Design in 2007 with a short film called Doxology, which went to a bunch of film festivals. Going to film festivals exposed me to more films like it and to all kinds of different ways of expressing myself through short films. That led to some career-making shorts and then making commercials based on those shorts and alternating making money and then not making money as we do in that kind of rollercoaster of creative life.

Jacob: Do you remember any specific ‘mechanical’ films that you were excited about?

Michael: Yeah. One of the filmmakers that felt special to me was Norman McLaren. He was a Canadian animator — I guess originally Scottish, but his career was in Canada — who was a big part of the National Film Board of Canada. He started working there in the 1950s and made a ton of really wonderful, very playful films that involved all kinds of experimental film techniques. Sometimes were strictly technical;; sometimes they were just beautiful aesthetic experiences; sometimes they had more meaning.

Michael: He got an Academy Award for a film called Neighbors. It was a pixelation film — which is like stop motion animation with people — about loving thy neighbor or killing them.

Jacob: Oh wow, yeah. I totally see the influence on your work. Also, it’s worth noting that this style looks commonplace now but was revolutionary at the time.

Michael: And then, one of the more inspiring film festivals in my early experiences was the Ann Arbor Film Festival. It is brutally experimental. Like, “Sit your ass in that seat. This shit is getting shown at you and fuck you if it's too loud for you, or too strobey or whatever because this is film is art!” It introduced me to a specific kind of filmmaking that is challenging and conceptual for the sake of itself. The abrasiveness is expected. But, Norman McLaren brought experimental film to the public and found a way to do it unpretentiously and bring people in and say, look, holy shit, what this can be welcome. I was really inspired by it.

Jacob: And, now, to backtrack, what exactly is “replacement animation.”

Michael: Replacement animation is when images are played in rapid sequence. Usually there’s a common visual element to unite the sequence. They’re usually roughly registered or positioned in the same place in the frame, but the actual image is different.It takes advantage of the persistence of vision and the fact that you can completely change an image frame by frame.

Jacob: I love that you found this very specific niche animation-wise. We’ve talked a lot about the interplay between the film and art worlds and your background really fascinates me because mine is similar but kind of opposite. I studied at USC’s film school, as well as the USC Roski School of Art & Design — but, I never really felt at home in the film school. To this day, I got an email from the Roski (the art school) congratulating me on having a doc short qualify for the Oscars, and the film school doesn’t even reply to my emails.

During my time at Roski, one of my favorite professors was Tad Beck who did some video art. Charlie White also taught a course, but I think it was only for graduate students. Otherwise, my college experience was very much film at the film school; art at the art school. Always separate. And, that’s not really the way my brain works. I want to combine them. I’m always a little jealous of people who went to actual art schools, so I'm curious about what the program was like at RISD and if they taught video in the art school.

Michael: I didn't have too many video classes outside of foundational stuff in my sophomore year because I went pretty whole hog on the animation program.So, like the big major is painting. Printmaking is a big one. The most like avant-garde major is glass blowing. There were a couple, but I don't know if vocational is the best term, but industry- or career-oriented programs. Architecture is serious. Industrial design is serious. Most of the other majors were “Art art,” including FAV (Film Animation and Video).

When I first toured RISD’s FAV program before college, I had just toured SCAD because I was interested in the technical stuff. SCAD has a Dolby mixing lab. I came to RISD, and I was like, “Where's your 5.1 lab?” The girl giving the tour said, “I don't know what that is, but this is a Steenbeck.” And I was like, “What the fuck is a Steenbeck?”

Jacob: And what is a Steenbeck?

Michael: A Steenbeck is an editing machine. It has reels of film that move across a tiny little projector, and it has a projection screen that's maybe 10 inches diagonal, where you can see your film right in front of you. You can chop the film, cut it, and splice it and immediately see what it looks like.

I think that they're phasing out film editing (or already have) in foundational film classes, which I think is such a crime. Not for nostalgia, but because of the value of learning to cut — understanding you have to feel it viscerally to commit to your choices. You have to think, “I’m gonna cut this piece of film in half right here and fuck up my film because it’s the right thing to do.” You know?

Jacob: Totally. When I came to USC, it was the first year they had removed actual film from the students' workflow, and I was so bummed about it.

Michael: RISD FAV was all about intuition. A bunch of my teachers had come through Cal Arts and learned from Jules Engel, this experimental animation-oriented guru over there.

My classes were all about validating the artist's intuition, and anything that came out was right. Sure, there was an editing process to filmmaking, but it was more like feeling around in the darkness for threads of light to pull down, weaving into a film, and finding ideas and feelings within yourself to get there.

It's inefficient and doesn't necessarily lend itself to films that hold together in a traditional way, but you end up with some pretty cool different stuff, and it teaches you to trust what's inside of you. Story was not a word that ever entered the classroom.

Outside of those classes, people tended to look down on conceptual art. Anytime a piece of art was overtly trying to make meaning, it was like, “Oh, God, what are you doing?! That’s not what art is for.” And that was me, too. I was in that camp. And many years later, I’m like, “Oh, God, it’s all about the meaning!”

Jacob: Obviously, both are important. But, yeah, there are people who do the opposite and jam meaning down your throat with the most traditional visuals possible.

Michael: And also, I mean, why are you making meaning? Are you making meaning to try and sound like what you’re doing is important because you’ve heard that what you’re talking about is important? Is it actually important to you? I think the key is, what emotionally resonates with your core?

What I’m trying to do now is find the things that are important to me, the ideas and the problems, and bring them out creatively and use the art skills to do that.

Jacob: That's fascinating. I feel like I've recently settled into the opposite but with kind of the same result. I found myself spending so much time trying to figure out “What’s the meaning? What do I want to say?” And that paralyzes me. So in the last few years I’ve settled into this – I guess I would call it trust – this trust that I am unable to make something that doesn’t have meaning. That I should just start making something that’s interesting to me for whatever reason and trust that by the end of it, it will have pulled the meaning or the feeling inside of me out so that it’s obvious. It’s the same end result, but I’ve taken a completely opposite path to get there.

Michael: That's the way we were taught to do it in school.Which is great. And, you can find doing it in school. I was doing that with Doxology. I didn’t know what the fuck I was doing, but I realized by the end “Oh, this is about your relationship with God and religion and bullshit.”

Jacob: It’s so interesting to me that our backgrounds are so similar but so different. You’re a filmmaker/artist who went to art school and got drilled in the art making side of it and now you’re re-embracing story. I’m a filmmaker/artist who mostly went to film school and had story and theory drilled into me. And, I’ve had to reacquaint myself with, like, “What is novel or delightful about this to me?” It’s just more proof to me that both are necessary and whichever way you’re trained, you’ll get pulled toward the other to balance it out.

Michael: I've taken a few classes from a story writing dude named Corey Mandel who I really, really, really, really, really have enjoyed learning from. He talks about the idea of the conceptual brain and the intuitive brain. And, if USC is hardcore conceptual and RISD is hardcore intuitive, like, you can integrate these things together and learn how to spend time in each zone when you need that feeling or input.

Jacob: That's super interesting. Okay, so when was the first time you encountered replacement animation?

Michael: My professors, bless them, would go off to animation and film festivals and see wonderful work and then bring it back to the classroom.

Jacob: Wow, that's huge. Especially pre-Internet.

Michael: Yeah, it was everything. The whole culture of swapping DVD screeners and before that VHS and God knows what else. Like, they brought back the film While Darwin Sleeps by a British filmmaker named Paul Bush. He made that in 2004. He’d spent some time in a museum full of insect specimens and used photographs of these similar insects to create shifting replacement animation of their forms. I thought it was so cool and so weird and different.

Michael: I thought that was super cool, but I didn’t do anything with it. I didn’t play with it myself. Then, my junior year I took a one minute animated film called Snail to . It was the first film festival I got into and went to. And, I went while I was working on Doxology. And it just blew my mind and everything. It was that experience of, you know, “10 films are just like, oh my God, what am I watching? And then the 11th was like, holy shit, I, I didn't know this was possible!”

Jacob: I always wonder about that kind of programming. The 11th film had a huge impact on you, but do you think that for someone else it was films one through seven were intolerable and number eight was the one that blew their mind?

Michael: Yeah. It's totally subjective.So, while I was at Ann Arbor, I saw a film called Market Street by a guy named Tomonari Nishikawa. It’s a black and white, silent, five minute replacement animation short shot on film that he shot going down Market Street in San Francisco. And, he’s animating the grates on the ground and the lamp posts and the wires and things like that.

Jacob: Wow, it makes my head melt to think about doing something like that on film.

Michael: Totally. I soon learned that when you're doing replacement animation, you get into a registration groove as you're shooting and you use the alignment marks and all the little lines in your viewfinder become hinges and become ways to line up different things frame to frame as you’re moving down the street. You’re kind of doing this improvisational animation. I don’t know if he had a digital process in there or had an optical printer but I doubt it. I think it was probably all in camera. And, it’s very very fast. It’s 24 frames per second, so it’s just buzzing.

Jacob: I know animation is frequently doubled from 12 frames per second to get 24 fps for playback. Is that true of replacement animation?

Michael: It varies. My favorite frame rate is 15 fps doubled to 30.

Jacob: Why 15?

Michael: 24 is so fast that your brain can’t appreciate the individuality of the images. 12 is so slow it feels clunky unless you’re really emphasizing each image. 15 just feels like the happy medium to me.

So, after seeing Market Street I was enamored with replacement animation. It just kind of knocked around in the back of my head for a while. Then, I brought Doxology to Slamdance in 2007 or 2008 and they commissioned me to make a short film for $99 – which was something called the Slamdance $99 Special. And, so I was like, okay, awesome. I'm gonna take my Canon DSLR and I saw Market Street before I lived in San Francisco but now I live in San Francisco… so I’m going to go make my Market Street.

I shot Dahlia with my DSLR and did a whole bunch of hyper stabilizing and repositioning of things. I did as much as I could in camera, but there's only so much you can do. Then I went through frame by frame and registered everything to, I think later, like they started to make these hypers where you start to get like stabilized.

Michael: Imagery in video and things start to look weird and interesting. And I'll pull in also. I had seen a film called Vision Point in School that used, it used I'll use the term hyper stabilization basically perfectly registering your image on a given point. And now you'll see this shit all over Instagram where like people's heads are like in just in one place while everything else is moving.

Michael: And so that idea of like being really careful with your stabilization and doing that by hand frame, by frame to get it perfect both in position and scale.

Jacob: For people who aren’t in animation, I don’t think they realize how time consuming this process is.

Michael: It's faster than hand drawn animation. That was one of the things I discovered in school. I don't love drawing, honestly. Like, I like drawing from life for fun. But I don't make characters. And in my early attempts to make any kind of like hand drawn animated… it wasn’t how I wanna pull my teeth. But, apparently, I am willing to pull my teeth compositing and re re-registering images and stuff like that.

And, you get into a groove, like your fingers are just doing the shortcuts and you're like, I'll the next frame, like, and and before you know it, you have some sequences. So I went out with the $99 and basically it just paid for. My friends to have some food while they watched my back in the middle of the night as I shot Dahlia in Golden Gate Park.

So, I took sidewalk cracks and parking meters and flowers and different recurring visual motifs of San Francisco and put 'em all together in kind of a love letter to San Francisco. I finished that and it premiered at Slamdance. I thanked Toka in the credit because Market Street had been so inspiring to me.

Jacob: Yeah. It's for sure like a riff on it, but it is, yeah, it's your version, but I see what you mean.

Michael: I say this because I started to feel possessive over a technique once I started working in it more. I still struggle with those feelings, especially with techniques. But, for better or for worse, they really don’t belong to one person. All our ideas can influence other people, and once AI starts to do its weird thing, anyway… you start to wonder where the lines are and how derivative works should be distinguished.

Jacob: Interesting.

Michael: And, so I went on to continue using replacement animation in some commercial stuff. I got to do a couple of ads for Art.com, which sells posters and can frame the posters for you. They had this massive catalog of basically every famous 2D work of art ever and said “have fun!” And, I just like did that kind of intuitive search through their collection looking for commonalities and patterns. You know, like, 15% of this stuff is naked women reclining and 10% is clocks, for example.

Jacob: It's data visualization in a way.

Michael: Yeah! So, ingesting all this stuff was a really fun process. So I had all the files and I would use folders as my light box.

Jacob: So you're just sorting all of, like looking through basically. Oh, I mean, ostensibly, if it's Art.com you ostensibly have access to, I mean, every, right? Like, from Mona Lisa to the Pink Floyd album cover that people get posters of for their dorm rooms.

Michael: Well, to be fair, it’s heavily European and American. But yeah, it’s a huge collection. My process started with categorization. Then, once I had categories I'd start to line them up in an After Effects sequence and play around with the patterns and shapes that started to emerge.

Jacob: Was that your process on Dahlia too? Or, were you just like, I'm gonna take a bunch of pictures and then see what I start finding. And at a certain point you kind of dialed or, you know, focus in and then let that be your guide? Or how, what, what is the what, what was the process on Dahlia and then how did it change for the Art.com piece?

Michael: I mean, similar processes where your exploration – whether of a city, or a catalogue of art — is finding what you think is interesting and lining it up and then just refine, refine, refine, refine, refine. And, you always end up with at least 50% more material than ends up in the thing.

Jacob: How long does something like that take?

Michael: It's not insane. It's, I, I wouldn't I would say that the whole thing was maybe like, I don't know, 300-400 hours. Most of my commercial work is so heavily previs-ed. So, we had a clear shot list going into the live action shoot.

Jacob: Oh yeah! This was live action — I’d forgotten.

Michael: Well, it’s animated, but it’s Pixilation. So, it’s using actual people as stop motion.

Jacob: And you’re not talking about images that are pixelated, right?

Michael: Pixilation predates the word pixelation. Pixelation is, yeah, when you have squares of, when you have visible pixels, pixelation. Pixilation was coined by Norman McLaren before pixels were invented… because he thought it made people look like Pixies.

Jacob: Oh wow that’s so silly.

Michael: Isn't it great? Technically, I don't know if this would be pixilation or basically this would be kind of a different kind of replacement animation maybe, but it's replacement animation with people. The focus is on the art, but because Art.com is selling things, it was important for them to all be in frames that you can actually buy.

Jacob: So walk me through your process on the shoot.

Michael: In pre-vis we picked all the pieces. I figured out what dimensions they’d need and what kind of frames would look good. We sent that info to Art.com and they built them all. On the day, we had maybe a hundred frames, and I assigned different frames to each image. We had an onion skin, like a semi-transparent frame by frame reference on set. So standing in front of the camera is a person holding a frame, that doesn’t have the actual image in it, because I was just going to comp that in.

I know that the frame is slightly smaller than the image that's going to go into it, so I can comp it without any issues. And then we just went through a cycle of, I don’t know, maybe 36 people or something and each new person would come in and line up the frame so I could see it on the monitor.

Jacob: I assume this is a still camera and something like Dragon Frame to track the onion skinning?

Michael: Yeah, we just spent the day like that. You can’t see it, I didn’t push it hard enough, but the sun is going buy in real time in the background of a real room.

Jacob: Wow, that’s a super cool level of detail. Okay, I want to shift a little to talk about the commercial side of it all. I’m curious how you went from making Dahlia to getting hired by Art.com. Did they reach out to you? Did you pitch and think, “oh, I want to use this style I did for Dahlia”? How did you become the go-to guy for replacement animation commercials?

Michael: I had a really fantastic situation with this company called Mechanism in San Francisco (which is now a big agency). There were conversations happening in the background that I wasn’t paying attention to half the time. The other half I was involved in a pitch process to clients. I had made Doxology in college and was kind of a go-to video guy for Upper Playground, this skateboarding and graffiti brand until I got laid off in the 2008 recession.

Michael: I don’t remember specifically, but I think I started a conversation with Mechanism through the online exposure for Doxology, which had gotten some nice love from Motionographer – which, especially at the time, was a big launching point for people.

As a result of being in Motionographer, a production company or aagency in Barcelona saw Doxlogy. And, instead of just ripping off my car/tango scene, they hired me to come out and replicate it.

Jacob: What a bunch of sweethearts for doing that. Like, to have the opportunity to rip you off like most companies will, and instead just hire you is just… God bless them.

Michael: Yeah. My producer was so scared when I landed. She was like, “Oh my God, you're so young.” And, and they like hired a more experienced guy to like sit over my shoulder in the edit just to make sure I wasn't doing anything wrong. He literally got paid to sit over my shoulder and I did the job.

After that job, I’d been talking with Mechanism and they said “let’s work together.

Jacob: Was it like a full-time creative job? Or just, “We're gonna use you when we can use you.”

Michael: It was framed as director representation. But, they didn’t represent me the way directors are traditionally represented where a brief comes in and you send your reel and if it gets selected you pitch on it. It was more client direct, which is the best.

Jacob: Oh yeah, that’s always a more secure and more creatively fulfilling way to work.

Michael: So Art.com came to Mechanical and said they wanted a brand anthem thing. They were like, “Well, Langan does this crazy shit and showed them Dahlia and talked about how we can use this technique with the art. I probably wasn’t involved in all the conversations that didn’t lead to jobs, but in this case, they were excited about the idea and I got brought in.

Jacob: That’s so great to have a relationship with a production company or agency that understands your skillset, when to bring you to the table, and how to create opportunities for everyone to get something out of it.

Michael: Yeah, I was like “this is Magic.” Art.com was great but a bigger example was for Pepsi. Mechanism was pitching Pepsi on a whole campaign for the Super Bowl half time show. Pepsi was the sponsor and Beyonce was the headliner. My buddy Tony, who is another director, was figuring out how we could use UGC combined with replacement animation.

Jacob: UGC as in User Generated Content.

Michael: Yeah. But UGC wasn’t a big thing quite yet. And there was just, you know, the stakes were so high. We had, I'm gonna look at my notes. We had 120,000 user submissions, and the campaign got five and a half billion impressions. So, like, most of the people in the world saw this one point.

Jacob: And, you directed a Super Bowl commercial!

Michael: Right, which I thought would secure my future.

[we both laugh… this industry is so unpredictable]

Michael: It was awesome. I went out and bought a nice turntable and a stereo and was like “I’m gonna take care of myself after this.” I decided to move to LA shortly after, and was like “I’m just gonna walk in and they're just gonna roll out the red carpet for me.” I thought that somehow I could parlay the idea of Super Bowl commercial into like any kind of commercial. And it doesn't necessarily work that way.

Jacob: Well, that’s the double edged sword of being known for a niche technique. If you’re the go-to guy and a Super Bowl commercial comes up in that style, you’re going to get the gig. But if you wanna do other stuff, people are like…. “Yeah, but he’s just the replacement animation guy.”

Michael: Well, I kind of abandoned the model I had been relying on, which was like making my own art, and then paid opportunities would come about as a result of me making stuff. Instead, I was like “I’m just gonna be reaching for things instead of creating things.”

Anyway, a couple years later, another RISD animation student, Conner Griffith, came out with a film called Ripple which used replacement animation in a way I’d always wanted to, but was afraid of. He took satellite photos from Google Earth and stuff, and and some of his own photography and wove these things together to create these beautiful synesthetic tapestries of replacement animation of the world as seen from above. I had thought about that but was afraid I’d get in trouble for copyright stuff.

Michael: It was so well done. A part of me was saying “Oh, fantastic. Look at all this new stuff!” But a part of me was also like, “Oh, but this is my domain.” I started to realize this niche wasn’t a thing I owned. We can all contribute to it, and maybe I’ve explored what I want to explore. At the time, I was also getting more interested and invested with stories.

Jacob: So were you just like, I’m done?

Michael: Well, I was in Los Angeles working for a visual effects company called Luma helping develop an original slate of films. I was busting my ass, but I was learning, and I was basically getting paid to learn about story.

A brief came in from a production company I was in touch with for a big Coca-Cola summer spot with replacement animation. People jumping into swimming pools, stuff like that. It was basically the best version that commercial replacement animation could be in my mind. And I was not interested in it at all.

They were like “But you’re the guy!” But, I was focusing on something else. That’s the moment I really understood that’s not where my heart was anymore. And that it was okay.

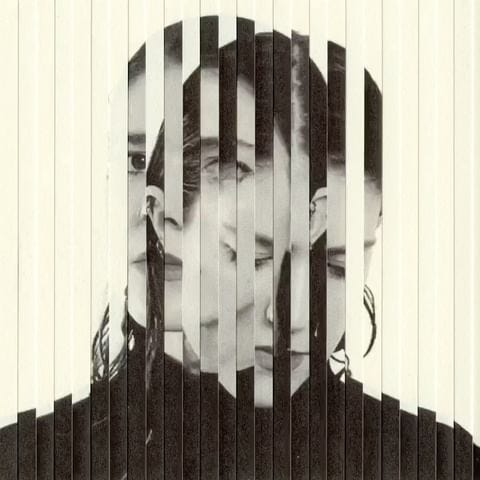

Jacob: That's fascinating for so many reasons. I had an experience recently that really inspired me to be more open minded about ownership. I learned about an incredible Austrian designer and printmaker based in Berlin named Julia Schimautz. She mostly does animation using Riso prints, but there was a quick ten second animation she’d done using printed and then shredded photographs.

Jacob: I was talking about making a video with a musician friend, and one song off his album really inspired me to riff on Julia’s technique. It’s a duet about a couple coming to terms with not being together, and I thought it would be really beautiful to visualize them in two separate spaces, overlaid with this technique. Literally in the same space, but unable to connect.

Jacob: I reached out to Julia and said, “Hey, I'm a director. I have a friend who's a musician. I saw this thing you did and — with your permission — I would love to expand on the idea for a music video.”

I don't know yet if I have a clear opinion about what’s right or wrong about riffing on someone else’s technique or style. I think my definition used to be 100% you don’t do that… and now it’s a little more like, I don't know, we're all kind of having a big visual conversation. Where I’m at now, I wouldn’t do it without contacting the artist. If she said no, that would have been it. But, her response incredibly gracious and high-minded. She’s like, “I made this, but you're an artist and you can riff on anything you see.” That's how I want to be with my work, but I'm not there yet.

Michael: That's so cool you got that response.

Jacob: Totally. On the previous video I made with this artist, my friend Philip, we featured a ton of memes and illustrations. And I reached out to every single person whose work we wanted to use and asked if we could use them in the video. Most people were down, some people said no, some were like “Hey, I made that for a company and weirdly don’t own it so I can’t give you the rights.”

Jacob: And I was just like, I'm asking, like, I'm not, like, they're like, if you, if you use it, I'm gonna come after you. And I'm like, if I was gonna do like I'm coming to you, why would, like, why are, anyway? But the, the other thing that, what you were just saying really made me think of is when you were talking about what's his face, McLaren and, and bringing these more experimental, visual, you know, styles or techniques or whatever to the masses.

Jacob: Commercial work is interesting because on the one hand, you’re mostly helping big corporations — many of which are actively fighting against our planet, against a living wage, treating people fairly, etc. — but on the other hand, those jobs are the ones that pay your bills. And, on top of that, because commercials are short form, there’s often an expectation that you have to be more visually artistic or experimental than you can be with narrative projects. And, why be protective when ultimately it’s a corporation that will own the work. Why not let other artists riff on it?

Michael: It is always evolving and I feel differently about something like visual echoes — a newer technique I’ve been working on — than I do about replacement animation because it’s still something I’m playing with and there are technical developments that are unique to me.

Jacob: Explain visual echoes.

LEFT OFF HERE

Michael: developments.

Jacob: when you say visual echoes, are you talking about like, like the turntable thing that you did? Is that a vi or what? What would you, what is visual

Michael: So the original technical term is actually chronophotography. That’s when it was using stills. Eadweard Muybridge was kind of adjacent to this technique. It was really developed as a scientific learning tool. You know, the classic image of studying how a horse moves.

Michael: The technique used strobe lights to juxtapose different moments in time, all in the same image. And, what you end up with is a kind of visual echo showing a progression of motion in animal or a person all in one frame together. McLaren riffed on this in 1968 with his film Pas de Deux. In 2010, my friend Tara Mayer and I made a film called Choros which was a riff on that technique, but using new technology and compositing techniques that weren’t available to McLaren.

Michael: There are definitely things I still would like to do to evolve that technique that are technically expensive and difficult. As cameras do more interesting things and our ability to record the volume of space changes, I’m excited to play with it. BUt, I know I’m going to see someone else do things first and I’ll just have to go “Oooh…” and keep walking.

Jacob: If someone came along and said, “Hey, we want you to take that style and do a soda ad…” Would you feel like this was your chance to put a budget behind something you’re experimenting with? Or would that feel too personal to do for a commercial?

Michael: It depends what it is. I've had that chance. I was developing a whole thing for a big client and it didn’t go. It’s hard. I really don't wanna make the world the worst place or cause too much more childhood obesity with my career.

Jacob: Okay, one last question before we wrap it up: Do you feel like there's a responsibility for artists when they're talking about these kinds of techniques to cite each other? The way you’ve been talking this whole interview, you source your inspiration really well. It’s almost like people giving the provenance of a piece of art, but for a specific technique.

Michael: I think that credit where credits due is really important. So often people just do a thing and don't mention anyone else who helped you make that thing, which includes people who you don't have a relationship with. If you're creating something where the general assumption is that you, like you came up with this amazing, beautiful thing and you're actually heavily referencing something else, it's absolutely imperative that you credit because like we all, we all need to support each other and help each other. I hope, for example, that more people employ Paul Bush to do commercials. I’d hate to steal a gig he was due.

And without that it's very easy for people to kind of just kind of wither away. And you know, I hope that more people employ Paul Bush to do commercials with replacement animation. I would hate to steal a gig that he was due, you know,

Jacob: Well, I really appreciate the way you talk about art. It’s a wealth of information, and I’m excited to go watch every video you referenced and go down those rabbit holes and be inspired. Thanks for chatting with me!

Michael: This was really, really fun. Thanks, Jake.

There ya go! Were you into this? Is this type of longer form content something you’d like to see more of on Jacob All Trades? Sound off in the comments!

And, before you go, here’s a quick plug for one of Michael’s latest films, coming soon:

Brilliant interview with a great artist, full of inspiring work. Thank you!